October 13, 1960. Game 7 of the World Series: Pittsburgh Pirates vs. New York Yankees. I left school on a run and raced up the hill to our house, where I found my mother—who never watched TV in the daytime—glued to the set. Ninth inning: the game was tied. At that moment, Bill Mazeroski smashed a home run out of the park. Mom and I screamed and jumped up and down as Pirate fans went beserk. The phone rang: my dad was calling from the office, over the moon. He’d grown up in Pittsburgh and was a life-long Pirates fan. Gritty, blue-collar Pittsburgh had beaten the stuck-up, entitled Yankees.

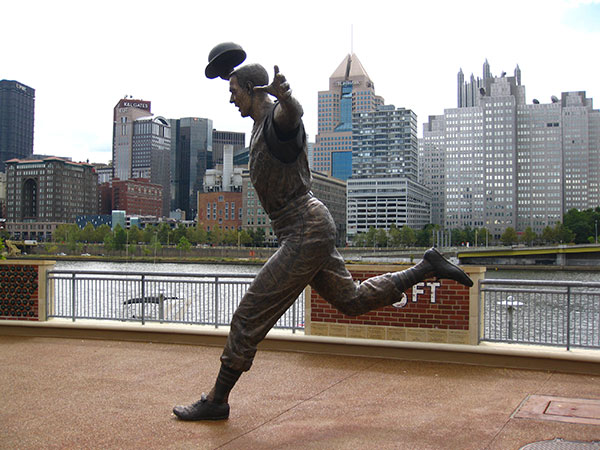

This statue commemorates Bill Mazeroski rounding second base after his series-winning home run for the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1960. Photo: Creative Commons BY 2.0

Mazeroski’s home run—famous as the one and only Game Seven walk-off win in World Series history—is my earliest, most memorable baseball memory.

Baseball was like background music in my family: always there. My dad, uncle, grandfather, and brother talked baseball and kept track of their teams. Dad alerted me to writers who wrote lyrically about the game. Without realizing it, baseball lingo and metaphors became imbedded in my brain. In high school, my boyfriend took me to a Red Sox game, where bleacher seats were $5, but I didn’t become a true fan until later in life. Raising my kids in Vermont without television, we didn’t see games often—though our neighborhood watched the debacle of the ’86 Sox/Mets series in a friend’s basement. I’m sure our screams of horror could be heard for miles when the ball skipped through You-Know-Who’s feet.

During my Vermont years, friends Rosie and Peter Shiras, ultimate Sox fans, talked baseball and urged me to follow the game. A Civil Rights activist, Rosie taught her students about baseball’s failure to integrate, as well as the Red Sox’s shameful distinction as the last team to sign an African American player. When she retired from teaching, Rosie’s students gave her a signed, framed Jackie Robinson baseball card. (Those who have read my baseball-themed novel, Out of Left Field, might recognize her card as that story’s endowed object.) Last year, I attended the annual game honoring Robinson at Fenway—the day when everyone in baseball, from players to coaches to the grounds crew, wears Robinson’s retired number 42. I raised my cup of beer to Rosie and Peter (RIP) in thanks for sharing their love of the game.

During my Vermont years, friends Rosie and Peter Shiras, ultimate Sox fans, talked baseball and urged me to follow the game. A Civil Rights activist, Rosie taught her students about baseball’s failure to integrate, as well as the Red Sox’s shameful distinction as the last team to sign an African American player. When she retired from teaching, Rosie’s students gave her a signed, framed Jackie Robinson baseball card. (Those who have read my baseball-themed novel, Out of Left Field, might recognize her card as that story’s endowed object.) Last year, I attended the annual game honoring Robinson at Fenway—the day when everyone in baseball, from players to coaches to the grounds crew, wears Robinson’s retired number 42. I raised my cup of beer to Rosie and Peter (RIP) in thanks for sharing their love of the game.

When I married a rabid Red Sox fan and moved to Boston, I became an ardent fan myself. Though baseball can be agonizingly slow compared to soccer (a game I also enjoy and have written about), I love watching a team come together through the season. I love the way Fenway Park feels intimate, even with 37,000 cheering fans, and it’s fun to see how the view of the game changes, depending on where you sit. The city and the region bond with the team, in ways that can be heartbreaking or magical. (That was most evident after an impossible World Series win, when much of New England went berserk with joy—but also after the horror of the Marathon bombings, when the team helped bring the city together.) I love the way the park erupts when a player makes a sensational catch or hits the ball over the Green Monster. I appreciate the smell of pretzels and French fries, the first sip of beer on a hot night, the sappy way we belt out “Sweet Caroline,” no matter the score. I’ve been in awe of the grace and intelligence of a pitcher like Pedro Martinez; I admire the grit of Dustin Pedroia, a small player with an outsize heart. For years, we celebrated the strength and dominant personality of David Ortiz—and now it’s a delight to watch fresh young talent coming up. Hope, despair, joy, tedium, pandemonium, astonishment, laughter—you can never predict what emotions will dominate on any given night.

When I married a rabid Red Sox fan and moved to Boston, I became an ardent fan myself. Though baseball can be agonizingly slow compared to soccer (a game I also enjoy and have written about), I love watching a team come together through the season. I love the way Fenway Park feels intimate, even with 37,000 cheering fans, and it’s fun to see how the view of the game changes, depending on where you sit. The city and the region bond with the team, in ways that can be heartbreaking or magical. (That was most evident after an impossible World Series win, when much of New England went berserk with joy—but also after the horror of the Marathon bombings, when the team helped bring the city together.) I love the way the park erupts when a player makes a sensational catch or hits the ball over the Green Monster. I appreciate the smell of pretzels and French fries, the first sip of beer on a hot night, the sappy way we belt out “Sweet Caroline,” no matter the score. I’ve been in awe of the grace and intelligence of a pitcher like Pedro Martinez; I admire the grit of Dustin Pedroia, a small player with an outsize heart. For years, we celebrated the strength and dominant personality of David Ortiz—and now it’s a delight to watch fresh young talent coming up. Hope, despair, joy, tedium, pandemonium, astonishment, laughter—you can never predict what emotions will dominate on any given night.

This year, in particular, baseball provides a much-needed escape from the horrors at home and in the wider world. We have tickets to a Sox-Cardinals game, the team we beat in the World Series after our eighty-six year drought. Like the narrator in my novel Out of Left Field, we’ll emerge from the concrete walkway where—as Brandon says—“The first sight of that green expanse, glittering in the sun, never gets old.” We’ll watch the players warm up, making lazy, impossibly long tosses across the field. We’ll find our seats, stand for the Star Spangled Banner, take that first sip of beer, and wait for the announcement we love: “Play ball!”

And the game begins.

When I married a rabid Red Sox fan and moved to Boston, I became an ardent fan myself. Though baseball can be agonizingly slow compared to soccer (a game I also enjoy and have written about), I love watching a team come together through the season. I love the way Fenway Park feels intimate, even with 37,000 cheering fans, and it’s fun to see how the view of the game changes, depending on where you sit. The city and the region bond with the team, in ways that can be heartbreaking or magical. (That was most evident after an impossible World Series win, when much of New England went berserk with joy—but also after the horror of the Marathon bombings, when the team helped bring the city together.) I love the way the park erupts when a player makes a sensational catch or hits the ball over the Green Monster. I appreciate the smell of pretzels and French fries, the first sip of beer on a hot night, the sappy way we belt out “Sweet Caroline,” no matter the score. I’ve been in awe of the grace and intelligence of a pitcher like Pedro Martinez; I admire the grit of Dustin Pedroia, a small player with an outsize heart. For years, we celebrated the strength and dominant personality of David Ortiz—and now it’s a delight to watch fresh young talent coming up. Hope, despair, joy, tedium, pandemonium, astonishment, laughter—you can never predict what emotions will dominate on any given night.

When I married a rabid Red Sox fan and moved to Boston, I became an ardent fan myself. Though baseball can be agonizingly slow compared to soccer (a game I also enjoy and have written about), I love watching a team come together through the season. I love the way Fenway Park feels intimate, even with 37,000 cheering fans, and it’s fun to see how the view of the game changes, depending on where you sit. The city and the region bond with the team, in ways that can be heartbreaking or magical. (That was most evident after an impossible World Series win, when much of New England went berserk with joy—but also after the horror of the Marathon bombings, when the team helped bring the city together.) I love the way the park erupts when a player makes a sensational catch or hits the ball over the Green Monster. I appreciate the smell of pretzels and French fries, the first sip of beer on a hot night, the sappy way we belt out “Sweet Caroline,” no matter the score. I’ve been in awe of the grace and intelligence of a pitcher like Pedro Martinez; I admire the grit of Dustin Pedroia, a small player with an outsize heart. For years, we celebrated the strength and dominant personality of David Ortiz—and now it’s a delight to watch fresh young talent coming up. Hope, despair, joy, tedium, pandemonium, astonishment, laughter—you can never predict what emotions will dominate on any given night.

Harvey Swados wrote about the working world. Before he was a published professor of writing, he worked as a metal finisher at a Ford Motor plant. His experiences there led to the publication of his story collection,

Harvey Swados wrote about the working world. Before he was a published professor of writing, he worked as a metal finisher at a Ford Motor plant. His experiences there led to the publication of his story collection,