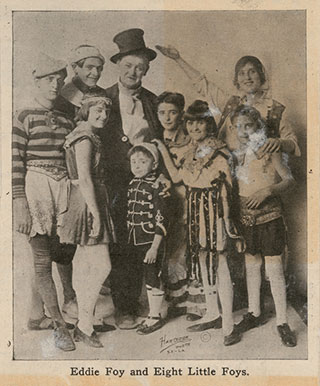

Family stories have inspired a number of my novels. Readers of this blog know that my great-grandmother’s elopement with a vaudeville musician led me to write The Life Fantastic. But my brother and I heard many other family stories, growing up.

A story written by one of my mom’s ancestors, James Ohio Pattie, played an important role in my first novel, West Against the Wind. My mom’s great-uncle Chuck Bray, hearing of my research into American pioneer history, sent me a copy of Pattie’s book, The Personal Narrative of James Ohio Pattie: The Adventures of a Young Man in the Southwest and California in the 1830s (the University of California Libraries has made the book available online through archive.org).

A story written by one of my mom’s ancestors, James Ohio Pattie, played an important role in my first novel, West Against the Wind. My mom’s great-uncle Chuck Bray, hearing of my research into American pioneer history, sent me a copy of Pattie’s book, The Personal Narrative of James Ohio Pattie: The Adventures of a Young Man in the Southwest and California in the 1830s (the University of California Libraries has made the book available online through archive.org).

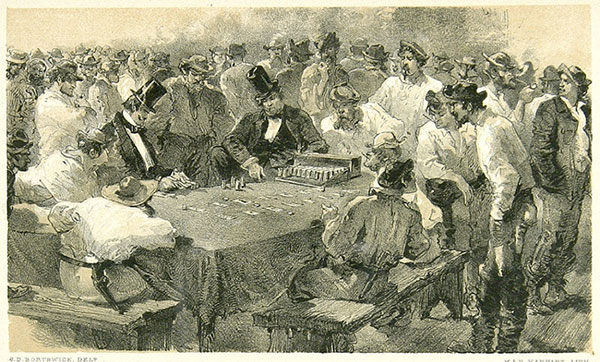

Pattie and his father, Sylvester, were fur traders and explorers before the opening of the Oregon Trail and the later stampedes of the California Gold Rush. When James returned to Missouri, he described his travels in a wilderness that was completely unfamiliar to most white Americans. According to Pattie’s account, he was the hero of every expedition, the savvy pathfinder when they were lost, the brave hunter who saved their party from a grizzly bear, and the keen-eyed miner who discovered a rich vein of copper in the mountains.

In spite of these obvious exaggerations, and my distaste over Pattie’s racist treatment of native people, his detailed descriptions of the west—written before photography was available—helped me to recreate the actual settings, wildlife, and physical challenges my characters encountered on the journey.

In spite of these obvious exaggerations, and my distaste over Pattie’s racist treatment of native people, his detailed descriptions of the west—written before photography was available—helped me to recreate the actual settings, wildlife, and physical challenges my characters encountered on the journey.

I even gave Pattie a cameo role as the crusty but friendly trapper who appears in West Against the Wind. He shares sound advice about the perilous ferry crossing ahead and recognizes my narrator’s resourcefulness as a trader.

(An amazing postscript to this story took place decades later. My husband and I were driving a scenic route from Tucson, Arizona to Mountainair, New Mexico, where our daughter-in-law was coring piňon pines for her doctoral research. We pulled over at a roadside attraction, and found ourselves on the precipice of a gargantuan copper mine. As I gaped at the size of the cratered landscape, John—who always reads historical markers—shouted: “Your ancestors were here!” I hurried over. To my astonishment, James Ohio Pattie and his father were memorialized on the sign, as the trappers who originally discovered the copper—just as Pattie had claimed. It’s hard to describe the mix of emotions I felt: despair and shame over the egregious mistreatment of the Apache and other tribal groups in the area; heartbreak over the rape of the landscape—combined with the stunned realization that my ancestor’s dramatic tale may have held more truth than I realized.)

To return to my mom’s family: by the time she was nineteen, my mom had lost her adored father and all four grandparents. But Mom brought our grandfather to life through stories focused on his sense of humor. She told us how he teased Weezie, our grandmother, by putting coat buttons in the collection plate at church, and how the neighbors loved his homemade bathtub gin.

We spent most summers with Weezie at her Vermont home. Though she insisted on high standards for us, she was famous for dancing on tables at parties during the Roaring Twenties. We even had a picture of her, dancing the Charleston in her flapper dress, with wineglasses at her feet. That photo, along with Weezie’s second marriage to my Grandpa Gil—which took place during a hurricane in Vermont—inspired my middle grade novel, Dancing on the Table.

We spent most summers with Weezie at her Vermont home. Though she insisted on high standards for us, she was famous for dancing on tables at parties during the Roaring Twenties. We even had a picture of her, dancing the Charleston in her flapper dress, with wineglasses at her feet. That photo, along with Weezie’s second marriage to my Grandpa Gil—which took place during a hurricane in Vermont—inspired my middle grade novel, Dancing on the Table.

On my dad’s side, I was lucky to know my grandfather, George Ketchum, for many years. He loved history in general, and also enjoyed sharing family history. He captivated us with stories about his peripatetic, hardscrabble upbringing. He told us that he was working as a court stenographer when he was “barely out of short pants”. A fine writer, he recounted his early years in an inspiring, personal memoir, “So When They Ask Me.” Though I haven’t drawn on Grandpa’s life directly, young characters in my stories often have jobs, such as selling newspapers (Amelia in Newsgirl), helping with sheep shearing (Gabriel in The Ghost of Lost Island) or working in a pizza parlor (Brandon in Out of Left Field).

My grandfather’s eccentric brother, Carlton, delegated himself the family historian. I treasure his cramped, handwritten letters, sharing details of our Randolph, Vermont ancestors. When Uncle Carlton learned I was writing historical fiction, he insisted that I had to tell the story of our Griswold ancestors: Joseph, a farmer, and his Pequot wife Margery, a midwife and healer. They settled in Randolph at the time of the American Revolution. Carlton sent me an article about this couple, as well as newspaper clippings about their life together. Those letters and articles sat in my “Idea File” for twenty years, until the Mashantucket Pequot Museum opened and I decided I could fictionalize their story. Where the Great Hawk Flies was the result. I’m only sorry that Uncle Carlton didn’t live to read the story that his demands inspired.

My grandfather’s eccentric brother, Carlton, delegated himself the family historian. I treasure his cramped, handwritten letters, sharing details of our Randolph, Vermont ancestors. When Uncle Carlton learned I was writing historical fiction, he insisted that I had to tell the story of our Griswold ancestors: Joseph, a farmer, and his Pequot wife Margery, a midwife and healer. They settled in Randolph at the time of the American Revolution. Carlton sent me an article about this couple, as well as newspaper clippings about their life together. Those letters and articles sat in my “Idea File” for twenty years, until the Mashantucket Pequot Museum opened and I decided I could fictionalize their story. Where the Great Hawk Flies was the result. I’m only sorry that Uncle Carlton didn’t live to read the story that his demands inspired.

I’m lucky that I could draw on rich family resources for my fiction. Now I think about the stories I’ve passed on to my own children and grandchildren. Which ones will they remember? And why?

When I married a rabid Red Sox fan and moved to Boston, I became an ardent fan myself. Though baseball can be agonizingly slow compared to soccer (a game I also enjoy and have written about), I love watching a team come together through the season. I love the way Fenway Park feels intimate, even with 37,000 cheering fans, and it’s fun to see how the view of the game changes, depending on where you sit. The city and the region bond with the team, in ways that can be heartbreaking or magical. (That was most evident after an impossible World Series win, when much of New England went berserk with joy—but also after the horror of the Marathon bombings, when the team helped bring the city together.) I love the way the park erupts when a player makes a sensational catch or hits the ball over the Green Monster. I appreciate the smell of pretzels and French fries, the first sip of beer on a hot night, the sappy way we belt out “Sweet Caroline,” no matter the score. I’ve been in awe of the grace and intelligence of a pitcher like Pedro Martinez; I admire the grit of Dustin Pedroia, a small player with an outsize heart. For years, we celebrated the strength and dominant personality of David Ortiz—and now it’s a delight to watch fresh young talent coming up. Hope, despair, joy, tedium, pandemonium, astonishment, laughter—you can never predict what emotions will dominate on any given night.

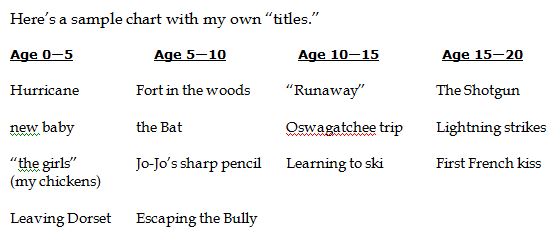

When I married a rabid Red Sox fan and moved to Boston, I became an ardent fan myself. Though baseball can be agonizingly slow compared to soccer (a game I also enjoy and have written about), I love watching a team come together through the season. I love the way Fenway Park feels intimate, even with 37,000 cheering fans, and it’s fun to see how the view of the game changes, depending on where you sit. The city and the region bond with the team, in ways that can be heartbreaking or magical. (That was most evident after an impossible World Series win, when much of New England went berserk with joy—but also after the horror of the Marathon bombings, when the team helped bring the city together.) I love the way the park erupts when a player makes a sensational catch or hits the ball over the Green Monster. I appreciate the smell of pretzels and French fries, the first sip of beer on a hot night, the sappy way we belt out “Sweet Caroline,” no matter the score. I’ve been in awe of the grace and intelligence of a pitcher like Pedro Martinez; I admire the grit of Dustin Pedroia, a small player with an outsize heart. For years, we celebrated the strength and dominant personality of David Ortiz—and now it’s a delight to watch fresh young talent coming up. Hope, despair, joy, tedium, pandemonium, astonishment, laughter—you can never predict what emotions will dominate on any given night. No matter what genre my students chose to explore as they wrote for young readers (picture books, fantasy, sci-fi, realistic or historical novels, mysteries or comedy), I urged them to find ways to reconnect with the experience of being a child or adolescent. This didn’t mean they should write “what really happened,” which can spell death for a story. But they needed to remember how it feels to live inside a child or adolescent’s body, to recall the emotions, physical reactions, thoughts, and sensations of a young person. In my first meetings with the students I worked with during the semester, I often gave them what I call The Title Exercise. (Adapted from an exercise by Ray Bradbury):

No matter what genre my students chose to explore as they wrote for young readers (picture books, fantasy, sci-fi, realistic or historical novels, mysteries or comedy), I urged them to find ways to reconnect with the experience of being a child or adolescent. This didn’t mean they should write “what really happened,” which can spell death for a story. But they needed to remember how it feels to live inside a child or adolescent’s body, to recall the emotions, physical reactions, thoughts, and sensations of a young person. In my first meetings with the students I worked with during the semester, I often gave them what I call The Title Exercise. (Adapted from an exercise by Ray Bradbury):

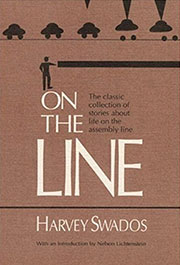

Harvey Swados wrote about the working world. Before he was a published professor of writing, he worked as a metal finisher at a Ford Motor plant. His experiences there led to the publication of his story collection,

Harvey Swados wrote about the working world. Before he was a published professor of writing, he worked as a metal finisher at a Ford Motor plant. His experiences there led to the publication of his story collection,

“Contrary to popular belief, Vaudeville was not wiped out by silent films. Many managers featured “flickers” at the end of their bills, finding them cheaper than the live closing acts that audiences walked out on anyway. Top screen stars made lucrative personal appearance tours on the big time circuits. So what killed vaudeville? The most truthful answer is that the public’s tastes changed and vaudeville’s managers (and most of its performers) failed to adjust to those changes.”

“Contrary to popular belief, Vaudeville was not wiped out by silent films. Many managers featured “flickers” at the end of their bills, finding them cheaper than the live closing acts that audiences walked out on anyway. Top screen stars made lucrative personal appearance tours on the big time circuits. So what killed vaudeville? The most truthful answer is that the public’s tastes changed and vaudeville’s managers (and most of its performers) failed to adjust to those changes.” Performers anxious to protect expensive costumes had bright red carpets laid between their dressing rooms and the stage. (This color made it easy to see if the carpeting was clean.) Only top headliners could insist on the red carpet treatment.

Performers anxious to protect expensive costumes had bright red carpets laid between their dressing rooms and the stage. (This color made it easy to see if the carpeting was clean.) Only top headliners could insist on the red carpet treatment.