Liza Ketchum

Question

Harvey Swados, your writing instructor at Sarah Lawrence College, sent you out into the world to observe and experience before you wrote. Can you share some of those experiences with us? Do you still work this way when you write?

Answer

When I enrolled in Harvey Swados’s creative writing class, I was a naïve young woman with little worldly experience. I wanted to write, but what would I write about? I knew nothing about Swados, but the class description was intriguing and something told me I needed that course. However, I was a transfer student and arrived to find the class had already filled. I was devastated. So I sat outside the classroom every day until Swados finally gave in and let me enroll.

Harvey Swados

Each week, Swados sent us into New York City on assignment. The city was just twenty minutes away by train, but the sites we visited were completely removed from our privileged campus existence. “Carry a notebook,” he told us. “Listen, ask questions, use your senses. And always bring a friend.” Turid Sato, my intrepid Norwegian roommate—who had crossed the Atlantic by freighter, and cross-country skied north of the Arctic circle—was the perfect companion.

Swados sent us to Night Court, a 24-hour courtroom where men and women were arraigned for shoplifting, assault and battery, and gun possession, under the weary gaze of a judge who’d seen it all. Turid and I visited the New York produce market after midnight and listened to grocers haggle with wholesalers over prices. We went to the Fulton Fish Market, at Manhattan’s tip, at four in the morning. There we watched burly men unload crates of fish and heave them into refrigerated trucks before stomping into the local diner. We followed them in, and ate the best pan-fried fish I have ever tasted. We also brought live lobsters home in paper bags—which caused a commotion on the subway when a loose claw started waving at our seatmate.

Harvey Swados wrote about the working world. Before he was a published professor of writing, he worked as a metal finisher at a Ford Motor plant. His experiences there led to the publication of his story collection, On the Line. The pieces we wrote for his class were full of gritty sensory detail, realistic dialogue, and interesting characters. While I didn’t become a reporter, as my friend Carter Stith did (for the St. Louis Post Dispatch), this class gave me the confidence to write non-fiction. And I learned the importance of immersing myself in the places that I wrote about; that no question is too dumb to ask; that most people enjoy talking about themselves, their lives, and their work.

Harvey Swados wrote about the working world. Before he was a published professor of writing, he worked as a metal finisher at a Ford Motor plant. His experiences there led to the publication of his story collection, On the Line. The pieces we wrote for his class were full of gritty sensory detail, realistic dialogue, and interesting characters. While I didn’t become a reporter, as my friend Carter Stith did (for the St. Louis Post Dispatch), this class gave me the confidence to write non-fiction. And I learned the importance of immersing myself in the places that I wrote about; that no question is too dumb to ask; that most people enjoy talking about themselves, their lives, and their work.

Since that class, I have always included workplaces in my stories and novels, and that includes work done by young characters as well as adults. The work may be incidental to the story—as Brandon’s work in a pizzeria is, in Out of Left Field—or the focus of an entire story, such as Newsgirl, where Amelia disguises herself as a newsboy in order to support her family, or The Life Fantastic, about Teresa’s struggle to become a star onstage. My novels have included a woman geologist and “powder monkey,” a photographer, a ticket seller at Fenway Park, a carpenter, a retired electrician, a newspaper editor who sets his own type, a social worker, a baker, a seamstress, a child who labored as an indentured servant (against his will), a Hollywood screenwriter, a banker, a sheep farmer, and a tattoo artist. (Thanks to Swados, I knew that I would have to spend time in a tattoo parlor, watching and asking questions, in order to create convincing scenes for Blue Coyote.)

Since that class, I have always included workplaces in my stories and novels, and that includes work done by young characters as well as adults. The work may be incidental to the story—as Brandon’s work in a pizzeria is, in Out of Left Field—or the focus of an entire story, such as Newsgirl, where Amelia disguises herself as a newsboy in order to support her family, or The Life Fantastic, about Teresa’s struggle to become a star onstage. My novels have included a woman geologist and “powder monkey,” a photographer, a ticket seller at Fenway Park, a carpenter, a retired electrician, a newspaper editor who sets his own type, a social worker, a baker, a seamstress, a child who labored as an indentured servant (against his will), a Hollywood screenwriter, a banker, a sheep farmer, and a tattoo artist. (Thanks to Swados, I knew that I would have to spend time in a tattoo parlor, watching and asking questions, in order to create convincing scenes for Blue Coyote.)

In addition to helping to reveal character, writing about a workplace allows the writer to use more interesting nouns and lively verbs, since every type of work has its own vocabulary. Most important: even the most tedious workplace could hold the spark that inspires a good story—and that’s a gift for the writer.

[For more about Harvey Swados]

Harvey Swados wrote about the working world. Before he was a published professor of writing, he worked as a metal finisher at a Ford Motor plant. His experiences there led to the publication of his story collection,

Harvey Swados wrote about the working world. Before he was a published professor of writing, he worked as a metal finisher at a Ford Motor plant. His experiences there led to the publication of his story collection,  Since that class, I have always included workplaces in my stories and novels, and that includes work done by young characters as well as adults. The work may be incidental to the story—as Brandon’s work in a pizzeria is, in

Since that class, I have always included workplaces in my stories and novels, and that includes work done by young characters as well as adults. The work may be incidental to the story—as Brandon’s work in a pizzeria is, in

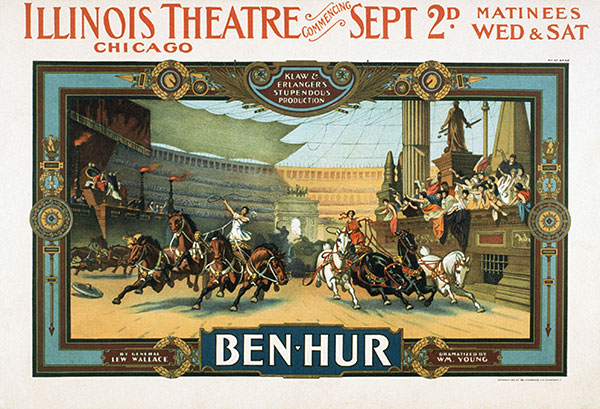

In The Life Fantastic, Maeve warns Teresa to be careful in her friendship with Pietro, an African American vaudeville performer. She tells Teresa that black men and boys in the South “get lynched if they look at a white girl.” Maeve also shares the story about a civil disturbance in Springfield, Illinois in 1908, where a white woman lied about being raped by an African American. Two black men were arrested, and when they escaped lynching, white residents rioted, causing massive destruction in the black community. The woman’s lie wasn’t discovered until after the riot ended and a number of people were killed. After that, Maeve’s father took part in Ku Klux Klan meetings.

In The Life Fantastic, Maeve warns Teresa to be careful in her friendship with Pietro, an African American vaudeville performer. She tells Teresa that black men and boys in the South “get lynched if they look at a white girl.” Maeve also shares the story about a civil disturbance in Springfield, Illinois in 1908, where a white woman lied about being raped by an African American. Two black men were arrested, and when they escaped lynching, white residents rioted, causing massive destruction in the black community. The woman’s lie wasn’t discovered until after the riot ended and a number of people were killed. After that, Maeve’s father took part in Ku Klux Klan meetings.

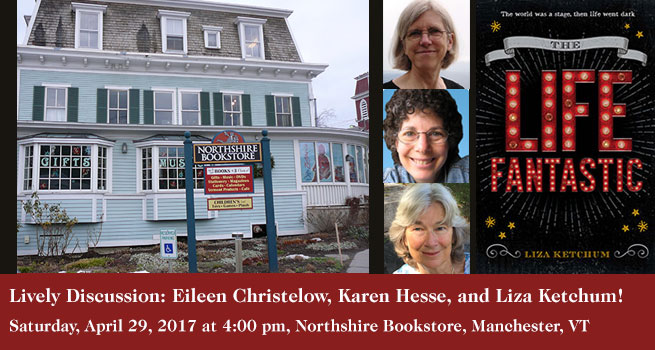

Please join us for a party to celebrate the release of The Life Fantastic: A Novel in Three Acts. The story takes place in 1913, at a time when vaudeville was America’s most popular form of entertainment. The book was inspired by a family story: Liza’s great-grandparents eloped and ran away to the vaudeville stage. In keeping with the vaudevillian backdrop of the book, the evening will include theatrical entertainment and music, as well as a reading and time for questions. The book has received kudos from teen readers as well as adults.

Please join us for a party to celebrate the release of The Life Fantastic: A Novel in Three Acts. The story takes place in 1913, at a time when vaudeville was America’s most popular form of entertainment. The book was inspired by a family story: Liza’s great-grandparents eloped and ran away to the vaudeville stage. In keeping with the vaudevillian backdrop of the book, the evening will include theatrical entertainment and music, as well as a reading and time for questions. The book has received kudos from teen readers as well as adults.