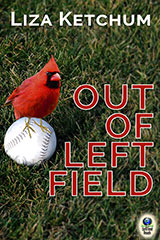

“Where on earth did you come up for the idea for this story?” A friend posed this question at a recent book signing for my novel, Out of Left Field. I explained how the story grew from a visit, long ago, to the D-Day cemeteries in France. But after the event, I realized that this question—or a version of it—is the one I hear most from audiences, whether the questioner is an eager first grader, an aspiring adult writer, or a curious reader. Often, I answer in relation to the specific book at hand, telling about a trip I’ve taken, or something I read in the paper, or an incident I’ve witnessed.

But questions, comments, or criticisms from readers have inspired me most over the years. Readers’ queries have led me to revise stories, to write sequels, or to create a new novel from scratch.

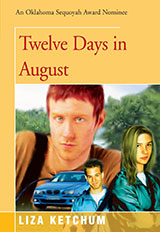

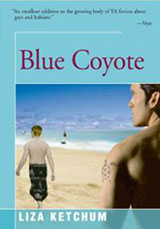

My young adult novel, Twelve Days in August, told the story of a high school soccer team and its struggles with homophobia and prejudice. The main character, Todd, finds himself in conflict with his peers and his own values; the book is really his story. Alex, a talented player (and secondary character) who is new in town, becomes the brunt of bullying and name-calling. Todd has to decide where he stands; his inner turmoil defines the novel. After the book was published, a number of readers wrote to me and asked: “What about Alex? Is he gay, or not?”

My young adult novel, Twelve Days in August, told the story of a high school soccer team and its struggles with homophobia and prejudice. The main character, Todd, finds himself in conflict with his peers and his own values; the book is really his story. Alex, a talented player (and secondary character) who is new in town, becomes the brunt of bullying and name-calling. Todd has to decide where he stands; his inner turmoil defines the novel. After the book was published, a number of readers wrote to me and asked: “What about Alex? Is he gay, or not?”

I didn’t know. But Alex intrigued me as a character, and I was also fond of his twin sister Rita, who had a minor part in Twelve Days. Since I often write books to answer questions that puzzle me, I decided it was time to tell Alex’s story. The result was Blue Coyote. For those who haven’t read the book, I won’t give away what happens—except to say that the novel faced challenges for its content. Those readers who asked about Alex pushed me to take risks, and I’m glad they did.

I didn’t know. But Alex intrigued me as a character, and I was also fond of his twin sister Rita, who had a minor part in Twelve Days. Since I often write books to answer questions that puzzle me, I decided it was time to tell Alex’s story. The result was Blue Coyote. For those who haven’t read the book, I won’t give away what happens—except to say that the novel faced challenges for its content. Those readers who asked about Alex pushed me to take risks, and I’m glad they did.

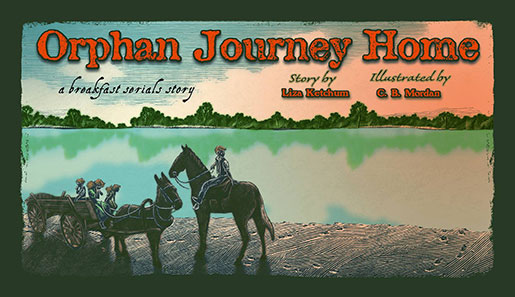

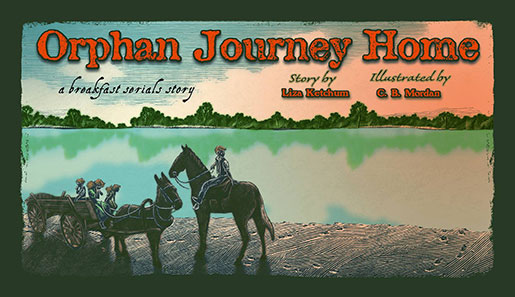

A different example of interaction with readers occurred when my novel, Orphan Journey Home, was appearing in serial form in newspapers across the country.

The story ran in weekly installments in over a hundred cities and towns, and readers wrote with questions and comments. The serial form was challenging to write: each chapter could only be 750 words and ended with a cliffhanger designed to entice the reader to buy the paper the next week. While the story was running, I received a contract to expand the novel for publication as a book.

illustration © C.B. Mordan

This was a unique opportunity. Expanding the story would let me fill in missing gaps in the plot, deepen the characters, and answer readers’ questions.

Usually, when a book is bound and printed, it’s too late to respond to readers. But as schools and libraries invited me to talk about the serial version, I jotted down their comments and questions. Some were factual, such as “What caused milk fever, anyway?” (It took me many months of research, and a moment of serendipity, to find the answer. See the Author’s Note in the book for the answer to that one!) One child wondered how Moses, whose leg was injured on the journey, managed to get crutches in the middle of the wilderness. (Good question!) After a talk I gave in Kentucky where I was puzzled about the route the children might have followed, a local historian sent me a map of the buffalo traces that became rough wagon roads.

The children in this story faced the danger of being “bound out”—kept as servants until they reached adulthood. They were also traveling from a free state (Illinois) to Kentucky, still a slave state in 1828. At one point in their travels, a black boy named George—who is bound out himself—helps the children escape from a man who wants to keep them. When I spoke to students at a library in Dayton, Ohio, an African American boy came up to me, at the end of the program, concerned about George. “Why couldn’t the kids take George with them?” Before I could answer, he figured it out himself. “Oh. Kentucky was a slave state. I guess it wouldn’t be safe to take George there.”

“What else could the kids do?” I asked.

He thought for a moment. “At least have them think about George again,” he said. “Maybe they could wish they had saved him.” What a great suggestion. Adding that emotional thread deepened the story.

Finally, one of the best questions I ever heard during a school visit came from a sixth grader. “What do you imagine you’ll be doing in ten years? What will you be writing?”

I was too surprised to come up with an answer. How could I predict the future? Now a decade has probably passed since he asked that question. I didn’t know then that I’d write two more historical novels before finishing a story about Red Sox baseball, the Vietnam War, and a boy in search of the truth about his family. (Out of Left Field). I wish I could thank that boy for his great question. I hope his own life has been full of adventure and promise.

I was too surprised to come up with an answer. How could I predict the future? Now a decade has probably passed since he asked that question. I didn’t know then that I’d write two more historical novels before finishing a story about Red Sox baseball, the Vietnam War, and a boy in search of the truth about his family. (Out of Left Field). I wish I could thank that boy for his great question. I hope his own life has been full of adventure and promise.

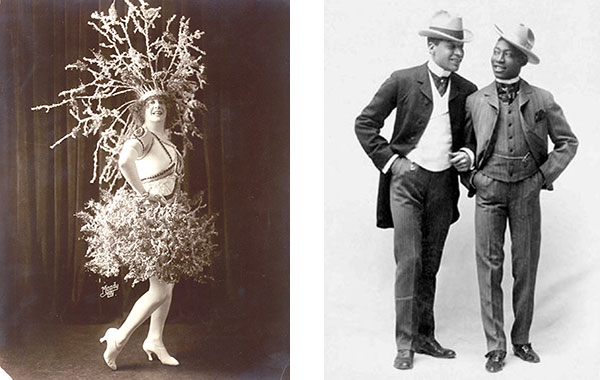

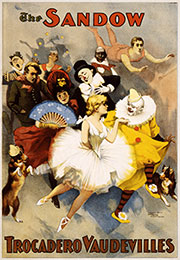

Burlesque originated in London in the 1830s and ran until the 1890s where it was most often a musical theater parody of a well-known play or opera or ballet. Brought to America in the 1840s, American Burlesque took a turn toward satiric and bawdy productions which usually incorporated exotic dancers. These performances were frequented by working-class men. Tickets were very inexpensive.

Burlesque originated in London in the 1830s and ran until the 1890s where it was most often a musical theater parody of a well-known play or opera or ballet. Brought to America in the 1840s, American Burlesque took a turn toward satiric and bawdy productions which usually incorporated exotic dancers. These performances were frequented by working-class men. Tickets were very inexpensive. “Vaudeville grew out of that burlesque tradition when Tony Pastor and E.B. Keith recognized, in the 1880s, that middle class families would come to their theaters, and create more profit, if they had classier acts that wouldn’t offend or scandalize women and children. Types of acts included popular and classical musicians, singers, dancers, comedians, trained animals, magicians, female and male impersonators, acrobats, illustrated songs, jugglers, one-act plays or scenes from plays, athletes, lecturing celebrities, minstrels, and movies.” (Wikipedia)

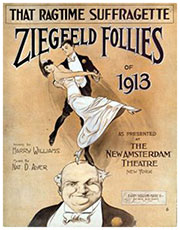

“Vaudeville grew out of that burlesque tradition when Tony Pastor and E.B. Keith recognized, in the 1880s, that middle class families would come to their theaters, and create more profit, if they had classier acts that wouldn’t offend or scandalize women and children. Types of acts included popular and classical musicians, singers, dancers, comedians, trained animals, magicians, female and male impersonators, acrobats, illustrated songs, jugglers, one-act plays or scenes from plays, athletes, lecturing celebrities, minstrels, and movies.” (Wikipedia) The Ziegfield Follies were on Broadway and then radio from 1907 to 1936. The costumes were lavish, the sets were splendiferous, and there were always Ziegfield Girls parading up and down long stairways in fanciful costumes. The acts were similar to those on the vaudeville stage. In fact, many performers moved easily from burlesque to vaudeville to Follies venues, especially the most well-known stars.

The Ziegfield Follies were on Broadway and then radio from 1907 to 1936. The costumes were lavish, the sets were splendiferous, and there were always Ziegfield Girls parading up and down long stairways in fanciful costumes. The acts were similar to those on the vaudeville stage. In fact, many performers moved easily from burlesque to vaudeville to Follies venues, especially the most well-known stars.

Liza, how did a dead canary inspire you to write this novel?

Liza, how did a dead canary inspire you to write this novel?

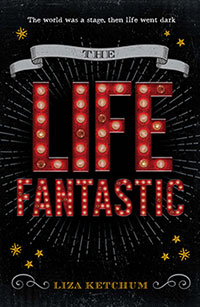

Liza, what is The Life Fantastic about?

Liza, what is The Life Fantastic about?