No matter what genre my students chose to explore as they wrote for young readers (picture books, fantasy, sci-fi, realistic or historical novels, mysteries or comedy), I urged them to find ways to reconnect with the experience of being a child or adolescent. This didn’t mean they should write “what really happened,” which can spell death for a story. But they needed to remember how it feels to live inside a child or adolescent’s body, to recall the emotions, physical reactions, thoughts, and sensations of a young person. In my first meetings with the students I worked with during the semester, I often gave them what I call The Title Exercise. (Adapted from an exercise by Ray Bradbury):

No matter what genre my students chose to explore as they wrote for young readers (picture books, fantasy, sci-fi, realistic or historical novels, mysteries or comedy), I urged them to find ways to reconnect with the experience of being a child or adolescent. This didn’t mean they should write “what really happened,” which can spell death for a story. But they needed to remember how it feels to live inside a child or adolescent’s body, to recall the emotions, physical reactions, thoughts, and sensations of a young person. In my first meetings with the students I worked with during the semester, I often gave them what I call The Title Exercise. (Adapted from an exercise by Ray Bradbury):

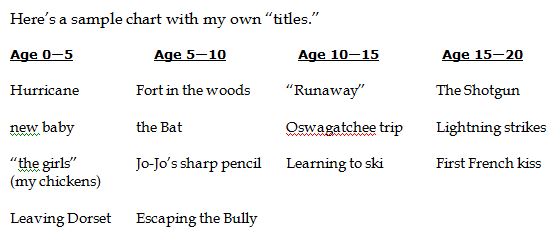

- Divide a piece of paper into four columns. Give each column a heading that corresponds to periods of your childhood. I suggest you split those early years into five-year sections: 0-5; 5-10; 10-15; 15-20, but you can divide them differently if you want. (See the sample chart, below.)

- Sit quietly and focus on each period for a few minutes. As memories come, jot down a title for each memory. For instance, when I focused on the ages 0-5, my titles were: “The Hurricane,” “New Baby,” “My Girls/Chickens,” “Leaving Dorset,” etc. Do this for each section, until you have four or five memories (or more) under each heading. You may find that more memories and titles emerge for one period; pay attention if that’s the case.

- Once you have some titles under each heading, circle those with the strongest emotional content. And remember: emotions can be positive as well as negative. Some memories may evoke joy, anticipation, pride, a sense of energy. Others bring up jealousy, fear, anger, sorrow, or shame.

- After you circle the most vivid memories, pick one you’d like to explore first. Free write for 15-20 minutes without stopping and ignore your inner editor. Writing in the present tense can make the scene more immediate. On the other hand, if the memory is frightening, embarrassing, or shameful, writing in the third person can feel safer, even liberating. You could also imagine that same experience from the point of view of someone else who was there. Use all your senses: smell, taste, texture, sound, and color. What emotions come up? Also—feel free to invent if you can’t remember exactly what happened. As my dear departed friend Ellen Levine used to say, “Factual memory is faulty; visceral memory is much more accurate.”

You may want to work chronologically, writing early memories every night for a week, grade school memories the next week, etc. Often, one particular period evokes a flood of feelings, images, and details. If you recall more events from ages eight to eleven, then maybe a middle grade novel is in your future. Maybe you’re one of the lucky ones with vivid memories from your preschool years—a huge asset if you decide to create picture books. If—as in my case—a part of you is stuck in adolescence, you may be more comfortable writing for young adults—at least for now.

You are creating a memory bank that you can draw on later. If you’re creating a scene in a story that involves a fight between siblings, a similar event in your past could allow you to portray the emotions more accurately. If you were bullied as a child, perhaps you can imagine what went on in the bully’s mind, if you wrote up the memory from his/her point of view. You never know what may come out of this exercise. In my case, writing about “The Shotgun” turned into a published short story many years later. Have fun!

Terrific, Liza! Thank you!!!