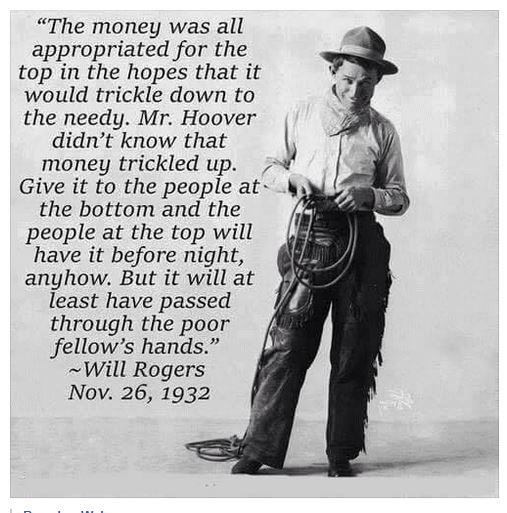

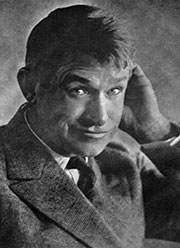

Will Rogers (photo: 1936, Clarence Bull, public domain)

Many famous performers of the 20th century—including stars familiar to me when I was growing up—started in vaudeville. Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, Charlie Chaplin, Ma Rainey, Bert Williams, Mickey Rooney, Jack Benny, and scores of others found early success on the vaudeville stage. I listed some of these luminaries in the Author’s Note of my new novel, The Life Fantastic, but after an email exchange with wise reader Vicki Palmquist, I realized I had omitted a performer with one of the most fascinating journeys: the comedian, “Ropin’ Fool,” columnist, and entertainer, Will Rogers.

Part Cherokee, Will Rogers grew up on a ranch near the Verdigris River in what was then Oklahoma Territory. He was lifted onto a pony as soon as he could walk, and was soon riding all over the ranch and roping cattle. He was incredibly skilled with lariat tricks, but his constant practicing got him expelled from boarding school. Home on the ranch, he perfected his roping routines and was soon performing in Wild West Shows that were popular at the time, calling himself “The Cherokee Kid.”

Drawn to vaudeville, Rogers brought Teddy, his cow pony, to New York City. After many rejections, he finally attracted attention when he and Teddy roped a crazed steer running loose in Madison Square Garden. The vaudeville theater impresario, Will Hammerstein, hired Rogers to perform on the roof garden of his Victoria Theater during the dead hours of 6-8 pm. Rogers and Teddy rode the elevator up to the roof and came out onstage together. (The pony wore felt boots so he wouldn’t slip on the stage floor.) Vaudeville revues often included a “dumb [silent] act,” which was Rogers’ role on the playbill. Calling himself “The Ropin’ Fool,” his intricate tricks were wildly popular.

One night, he made a mistake and commented on it, earning a laugh from the audience. Soon, he was making jokes as he roped. As his reputation grew, he was hired to perform with the Ziegfield Follies, the city’s most lavish and spectacular theatrical revue. Ziegfield expected Rogers to perform silently while his actresses (billed as “The Most Beautiful Girls in the World”) changed their costumes. But Rogers began to comment on the news as he twirled his lariat—and the audience loved it. He learned that he couldn’t tell the same joke twice, so he read many editions of the local papers, jotting down jokes to use that night. Since Ziegfield expected Rogers to be a silent entertainer, he was furious—until he watched a show and heard the laughter. He then gave Rogers top billing.

Will Rogers’ motto became, “All I know is what I read in the papers.” Eventually, he turned his onstage commentary into a daily column that was carried in 500 papers, six days a week. He wrote his columns on a portable typewriter, composing on trains, in cars—and even on the single-engine plane that carried him to his death in Alaska. His humorous, down home philosophy appealed to millions of Americans and buoyed them up during the Great Depression. When he died, the country went into a deep mourning that many compared to the aftermath of Lincoln’s assassination.

Rogers’ trajectory was amazing. The “Ropin’ Fool” became a stand-up comedian, film star, public speaker, and writer; the most-read columnist in America. He assumed—correctly—that most Americans read the daily newspapers, so they would get his jokes. Many of his commentaries on government and politicians are eerily apt for the present time. And he managed to poke fun without vitriol. Rogers claimed, “I don’t make jokes. I just watch the government and report the facts.”

When my sons were young, we spent a year in southern California. We often drove out to Will Rogers’ ranch—now a state park—to kick a soccer ball around or take a hike. Inside Rogers’ comfortable ranch house, decorated with mementos from his career, we could see the balcony where Rogers stood and threw his lariat, lassoing house guests as they passed through the living room. As our country suffers through a dangerous, partisan era, I’m reading his commentaries with a wistful longing for his gentle, yet pointed humor.

When my sons were young, we spent a year in southern California. We often drove out to Will Rogers’ ranch—now a state park—to kick a soccer ball around or take a hike. Inside Rogers’ comfortable ranch house, decorated with mementos from his career, we could see the balcony where Rogers stood and threw his lariat, lassoing house guests as they passed through the living room. As our country suffers through a dangerous, partisan era, I’m reading his commentaries with a wistful longing for his gentle, yet pointed humor.

(Full disclosure: I’m lucky to have the perfect resource on my shelf, a biography of Rogers written by my dad, Richard M. Ketchum: Will Rogers: His Life and Times. American Heritage Press, 1973.)

[post_footer_TLF]

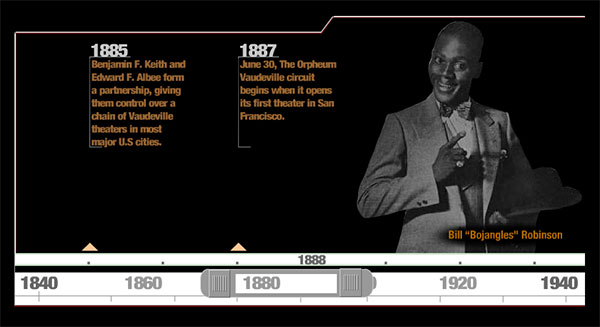

With Teresa determined to sing on the vaudeville stage, she was looking for work in what was viewed as a more wholesome environment than the entertainment that had gone before. Vaudeville began in the 1880s and ended in the 1930s with the advent of widely distributed film and radio.

With Teresa determined to sing on the vaudeville stage, she was looking for work in what was viewed as a more wholesome environment than the entertainment that had gone before. Vaudeville began in the 1880s and ended in the 1930s with the advent of widely distributed film and radio.

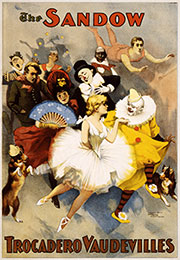

Burlesque originated in London in the 1830s and ran until the 1890s where it was most often a musical theater parody of a well-known play or opera or ballet. Brought to America in the 1840s, American Burlesque took a turn toward satiric and bawdy productions which usually incorporated exotic dancers. These performances were frequented by working-class men. Tickets were very inexpensive.

Burlesque originated in London in the 1830s and ran until the 1890s where it was most often a musical theater parody of a well-known play or opera or ballet. Brought to America in the 1840s, American Burlesque took a turn toward satiric and bawdy productions which usually incorporated exotic dancers. These performances were frequented by working-class men. Tickets were very inexpensive. “Vaudeville grew out of that burlesque tradition when Tony Pastor and E.B. Keith recognized, in the 1880s, that middle class families would come to their theaters, and create more profit, if they had classier acts that wouldn’t offend or scandalize women and children. Types of acts included popular and classical musicians, singers, dancers, comedians, trained animals, magicians, female and male impersonators, acrobats, illustrated songs, jugglers, one-act plays or scenes from plays, athletes, lecturing celebrities, minstrels, and movies.” (

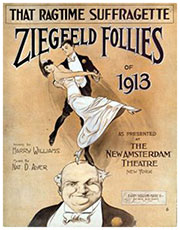

“Vaudeville grew out of that burlesque tradition when Tony Pastor and E.B. Keith recognized, in the 1880s, that middle class families would come to their theaters, and create more profit, if they had classier acts that wouldn’t offend or scandalize women and children. Types of acts included popular and classical musicians, singers, dancers, comedians, trained animals, magicians, female and male impersonators, acrobats, illustrated songs, jugglers, one-act plays or scenes from plays, athletes, lecturing celebrities, minstrels, and movies.” ( The Ziegfield Follies were on Broadway and then radio from 1907 to 1936. The costumes were lavish, the sets were splendiferous, and there were always Ziegfield Girls parading up and down long stairways in fanciful costumes. The acts were similar to those on the vaudeville stage. In fact, many performers moved easily from burlesque to vaudeville to Follies venues, especially the most well-known stars.

The Ziegfield Follies were on Broadway and then radio from 1907 to 1936. The costumes were lavish, the sets were splendiferous, and there were always Ziegfield Girls parading up and down long stairways in fanciful costumes. The acts were similar to those on the vaudeville stage. In fact, many performers moved easily from burlesque to vaudeville to Follies venues, especially the most well-known stars.

Liza, how did a dead canary inspire you to write this novel?

Liza, how did a dead canary inspire you to write this novel?